Primary lens: Evolutionary psychology

Secondary lens: Cognitive psychology

The afterhours of What Ifs

Our contractual hours may be over, but the cognitive overtime has only just begun. It was never part of the agreement, no special clause in the paperwork we signed — yet the mental and existential labour we continue to exert, unpaid and uninvited, persists.

We rehearse tomorrow’s presentation on the way back home, lips moving silently between strangers, weighing each word like currency, calculating its emotional yield. We choose what to say and what to omit, hoping to buy influence, approval and belonging — an intangible acknowledgement that means we’ve done enough, that we are enough. Later, we give our spouse the 'Darling, I’m home' kiss, attempting to stage presence while knowing full well our minds are still elsewhere, tangled in the echo of a client’s 'Fine' that felt anything but. Eventually we make our way to bed, hoping the day and the cognitive overload it ushered may finally be over. But as the head descends onto the pillow we soon realise the mind has other plans — a long itinerary of unresolved thoughts and encore performances.

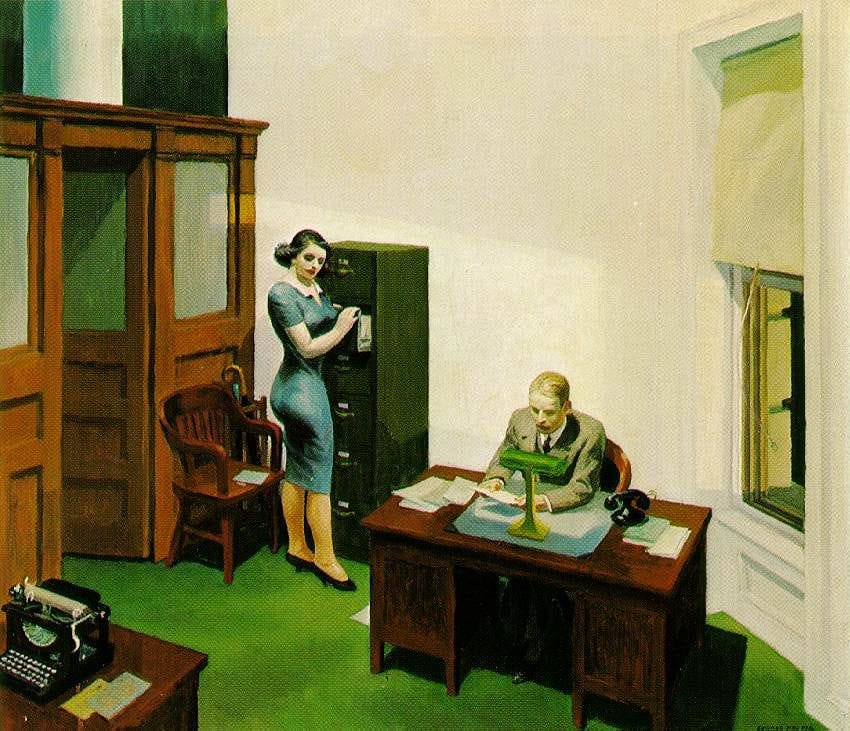

Like the figures in Hopper’s Office at Night we remain lit up long after the world has quietened, illuminated not by fluorescent light of office lamps but by the flicker of mental rehearsals and emotional reruns. Thoughts come and go in a chaotic choreography of what-ifs, each one stepping in uninvited, each one demanding its moment. We long to disconnect, to shut down the stream of consciousness and, at last, fall asleep.

We fail. Quietly and repeatedly.

As the night advances, governed by the silent rhythm of celestial bodies indifferent of our sleeplessness, we continue to lie, alert and vigilant, our minds staging encore after encore. Somewhere between the recollection of that moment when everyone was silent as we delivered the punchline and the fact that nobody acknowledged our memo later in the day an unexpected thought dares sneak in — not loud, not dramatic, just quietly insistent: 'Why is it so hard to let go?'

The ancient clock that keeps us awake

We are often told that we can do anything, that nothing is impossible and almost everything is within reach. The seductive promise of unbounded agency and our brain's capacity to regulate our thoughts, feelings and behaviours isn't new. This notion of brain-as-machine can in fact be traced as far back as the early Enlightenment when the ideas of the mechanistic universe became the dominant paradigm of the Western civilisation.

The mechanistic universe, as imagined by great thinkers like Newton and Descartes, cast reality as a grand clockwork: predictable, measurable and governed by immutable laws of nature. In this view, the mind was no exception: conceived as a powerful and rational engine, capable of calculations, control and refinement. This framework didn’t just shape science; it quietly reshaped how we imagined ourselves — rational beings, sovereign over emotion and fluent in self-command (Schultz and Schultz, 2015).

Later, as the technological advancement and the cognitive revolution ascended, gradually eclipsing the fading ideas of the Industrial Age, a renewed faith in mental mastery took hold. Inspired by the ultimate marvel of the late 20th century — the computer — we embraced a pervasive, though ultimately unhelpful, belief that the brain, like a machine, could be endlessly upgraded and optimised for performance.

It is no surprise, then, that in moments when we long to disconnect from the travails of the day just gone, we find ourselves perplexed. Unlike the machines that run on binary code, the mind offers no simple switch. It hums on — rehearsing, revisiting, refusing to power down — driven not by circuitry, but by mechanisms more ancient than the cog and the chip. Constructed by the immutable forces of nature across the vastness of the foggy rainforest, these forces, like the minute hand of a clock, ensure we remain in motion — scanning, adapting, surviving.

Primordial rhythms of the modern work

The world of work as we know it today appears vastly different from what we might imagine it looked like millennia ago, when our forebears lived and toiled beneath the canopy of the rainforest. The habitat that surrounds us reinforces this illusion of rupture: the tall, glimmering towers of Faria Lima in São Paulo — complete with CCTVs, boardrooms, and vending machines — stand in sharp contrast to the early settlements scattered across the Amazon jungle. Popular culture, too, is quick to offer nostalgic visions of a simpler past — one without late-night emails, working through the weekend or the quiet compulsion to appease the board.

But the difference, it turns out, is not as vast as it seems, and the truth — brutal, yet oddly comforting — is that like us, our ancestors didn’t clock out at 5pm either, and the Neoliberal Age bears more resemblance to the Stone Age than we often acknowledge. Perhaps the journey to quieter nights and quieter minds isn't solved by asking a search bar how to switch off, but with a return to something older. Could it be that the sleeping aid we need isn’t pharmacological, but psychological — the one that's not prescribed, but discovered through reflection on the origins of our species’ endless worries, its existential angst: scripted, embedded and passed down through the relentless course of evolution.

We like to think, pepped by the engulfing narrative of the neoliberal order, that our actions, and their consequences, are ours entirely; that we are the masters of our fortune. But beneath the surface of this comforting myth lies a deeper revelation: much of what we do isn’t something we authored, but inherited, often from those we didn’t even know. This collective, intergenerational memory continues to guide our lives, often at the expense of our happiness and peace of mind. It is perhaps even more sobering to realise that these properties — being happy, feeling tranquil — are, and likely never were, on our brain’s agenda. Survival, however, is another matter entirely.

Hunger code

To survive on the ancient savanna, where food chains were short and the time between the mammoth’s fall and its roasting by fire even shorter, dieting wasn’t an option and calories didn’t count. We ate when we could, never certain when another meal might come — or if it ever would. Today, that once vital adaptation often becomes a burden, through no fault of our own (Buss, 2024). Bound by ancient wiring we’ve yet to fully understand, we continue to confuse a missed email with a missed opportunity, as though the inbox were a hunting ground. We scan our inboxes midway through the new episode of our spouse’s favourite series, becoming prisoners to phantom alerts — not because we want to, but because we cannot yet rewrite the ancient code. And when the soft chime of a new message finally arrives, it hijacks the same reward circuitry that once flared when a colossal, fur-covered Pleistocene giant collapsed at our feet, promising satiety, survival and, if fortune allowed, successful reproduction.

Leaveism

Sometimes, we opt to work through the weekend and bristle if interrupted. The needs of those in close proximity — a loving spouse, a trusted friend, a helpless child — make way for matters more serious, more urgent. Or so we tell ourselves.

'Daddy needs to work - why don't you play with your Legos?'

'I have to finish this, sorry.'

'I can't make it - got lots of work to do. How about next week?'

Organisational psychologists refer to this as leaveism (Hesketh, 2013), the quiet colonisation of personal time by professional obligation, often self-inflicted. This practice, maladaptive on nearly every dimension, is particularly prevalent and thrives in environments where vulnerability is penalised, rest pathologised and constant availability is worn like a badge of honour. But what masquerades as dedication is, upon closer inspection, often a reflection of primordial instincts and a persistent fear of being left behind. In modern-day São Paulo, solitude is rarely, if ever, a treat to existence. Our brains, however, are yet to evolve in step with the realities of technological advancement, which has far outpaced the development of our cognitive architecture.

Unlike our ancestors, who relied on their tribe to survive in the shadows of the ancient rainforest, our need to be seen as indispensable has diminished, but the awareness has yet to settle within us. And so we continue to send signals to those in distance offices, sometimes across the continents, that we are here, available, at their service and disposal. And we forget that those in close proximity, dismissed as less serious and less urgent, are the only ones who will be there, holding our hands when the cogs of our biological clock finally come to a stop. We continue to polish that deck, working through the late hours on a Saturday night, unaware that twenty years from now the only people who will remember us working late will be our children.

Taming the instinct

The cognitive revolution and the worldviews it fostered, remains the dominant lens through which we continue our tentative attempts to understand what it means to think, feel and act as Homo Sapiens. Although many questions remain unanswered and scientific discoveries often contradict one another, the quest for clarity continues, with the metaphor of brain-as-computer still reigning supreme. Decades after the onset of the first computational models of human condition we are yet to find the elusive switch — the one that might, at will, gently sever and separate the sorrows of work from the rest of our lives. Cognitive psychologists, brilliant but not infallible, may never find a way to compartmentalise personal and working identities but over the years, they've provided us with a few interim solutions.

The Echo book

When intrusive thoughts arrive — often uninvited, late at night or midway through a quiet dinner — it may be helpful to write them down. Not to discard, but to fossilise. The echo book that we create becomes a ledger of fears, grievances, and unresolved loops: a place to deposit what cannot yet be resolved, but must be acknowledged, preferably on the spot. We won't publish this book — though that, too, could become a form of defiant liberation — but will keep it as an intimate mirror into what it feels like to inhabit this singular, sentient life of ours. Psychologists call this technique cognitive offloading (Risko and Gilbert, 2016), a form of expressive writing that externalises internal tension and supports emotional regulation. By translating thought into ink, we reduce cognitive load and create space for rest. The brain, after all, is designed to generate ideas — less so to store them. And so we write, not to forget, but to return later, when the time is right. It is not deletion, but a kind of symbolic archiving, like dragging a folder from the desktop into a quiet subdirectory. The contents remain intact, untouched and waiting. We do not erase; we simply refile, so that the screen of the present can stay clear enough for us to enjoy.

The hierarchical hijack

Sometimes, we can reverse-engineer our ancient instincts with a single question: Who is the most important person in my life right now? Is it the managing partner across the office floor, the client in a distant city, or the person — beautiful, kind and quietly waiting — who sits across from you at the dinner table they so lovingly laid out? Our brains evolved to seek status and proximity as survival cues, but in the modern age, these instincts often misfire. By consciously reordering the hierarchy of attention, a process that is known in psychological circles as cognitive reappraisal (Gross and John, 2003) , we reclaim presence and remind ourselves that proximity is not just physical — it’s emotional, relational, sacred. We do not always choose where our attention lands, but we can choose what we honour and entertain. In that quiet act of reordering, we soften the grip of illusory urgency and allow true meaning to rise. The dinner table becomes more than a setting — it becomes a signal, a sanctuary, a gentle rebellion against the external noise. And in recognising who truly matters, we do not diminish ambition; we simply remind it where to bow.

Restorative Language

Of all species on this lonely planet, adrift in the vastness of the infinite cosmos, Homo sapiens alone developed a language so intricate it enabled us to survive the raw ecologies of early Earth, the elemental landscapes that shaped our minds and bodies, and carry our civilisation into outer space (Harrari, 2015). It is, thus, possible that language could once again become our salvation when the ancient instinct that mistakes productivity for safety and belonging takes hold. The conversations we have — with a friend in a lavish café along the Oscar Freire, with a colleague aboard the plane taking off for distant lands or with a spouse at dinner table, set quietly in the back garden — can become a symbol of our conscious resistance. The recounting of what happened at work becomes a reminiscence of the first holiday we took when we were twenty. The conquered inboxes make way for the dreams of conquering fears we've long been harbouring deep inside. The dreams of promotion recede, opening avenues for a dreams of a life together — in places we've never visited and the ones our work will never take us to.

This is not escapism, but restoration, the kind that reconnects us with identity beyond productivity and reminds us of the quiet truths that shape who we are — not the output, but essence. And in doing so, we create a space where the self is not measured, but remembered by those who truly matter, yet will never appear in the corporate slide deck.

Margins and marginalia:

- Buss, D. M. (2024). Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind (7th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003230823

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

- Hesketh, I., & Cooper, C. L. (2014). Leaveism at work. Occupational Medicine, 64(3), 146–147. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqu018

- Risko, E. F., & Gilbert, S. J. (2016). Cognitive offloading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(9), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.06.004

- Schultz, D. P., & Schultz, S. E. (2015). A History of Modern Psychology (11th ed.). Cengage Learning Custom Publishing.

- Harari, Y. N. (2015). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Harper.

Discussion