It begins with small talk. Late afternoon light spills through the marquee, catching the bubbles rising in a glass. Laughter swells near the dance floor, tapering into smaller conversations. Two guests talk idly about the canapés and the couple’s honeymoon plans until the pause arrives – that small, expectant moment when, inevitably, the question appears: ‘So, what do you do?'

For years, the answer came easily. ‘I’m in finance.’ ‘I’m a GP.’ ‘I run a small publishing house.’ A neat label that required little, if any, further explanation – a statement usually met with a familiar nod and the reflexive ‘Nice’ – a well-rehearsed exchange of polite pleasantries that keeps the social machinery running.

But tonight, the words falter and the familiar shorthand feels foreign. Saying ‘I’m retired’ would be accurate enough, yet it doesn’t feel right – true, but somehow not the whole truth, and we can’t quite explain why. There’s a pause, just long enough to notice. Our eyes drift as we are searching for something to say before landing on a polite half-answer. It fills the silence but doesn’t quite convince, so we follow it quickly with the familiar deflection – ‘So, how about you?’

The spotlight shifts, relief disguised as curiosity.

We listen, we nod, yet part of the mind has already slipped away, circling a question that feels as much philosophical as psychological: who are we when work no longer explains us?

It seems trivial, this momentary awkwardness, yet it exposes something larger. Our occupations are not merely professional coordinates that tell others what we do; they are social scripts – the ones that tell others, and ourselves, how to place us in the social world: what to expect of us, what to assume of us, what to make of us.

We thought we had done everything right: consulted advisers adorned with postnominals, invested for the long term and planned withdrawals with care. The picture of prudence on paper. Yet, for all that financial foresight, there’s often a quiet psychological underinvestment. We assume a well-designed cash flow will guarantee a well-lived life, only to discover that a true retirement portfolio includes more than money. It requires capital invested in who we are, not only what we own.

The self as a portfolio

We tend to think of diversification as a financial principle – a way to spread risk and steady returns. Yet it may be just as useful as a psychological one. If all our identity capital sits in a single stock – our work – then retirement can feel like a market crash. To spare ourselves that kind of collapse, the antidote is often the same as in finance: to keep investing elsewhere, steadily and quietly, cultivating a portfolio of selves that can withstand correction without collapse.

Psychologists have long suggested that a healthy identity is made up of multiple self-aspects – the different roles, relationships and contexts that make up who we are. We might be a headteacher managing inspections, a parent managing teenagers, a volunteer who helps run the Sunday lunch at the church hall. Each asks for a different version of us and that variety keeps the self intact.

When these self-aspects are numerous and distinct, we achieve what psychologists call high self-complexity – a richly layered sense of identity built from many parts, each helping preserve our overall stability when one is shaken. Losing a job or leaving a profession hurts, but the blow doesn’t destroy the whole structure because other roles continue to anchor who we are. In contrast, low self-complexity means our roles overlap heavily or revolve around a single theme. When that theme disappears, the whole system can falter – emotionally, socially and even physically.

The idea comes from Patricia Linville, a psychologist who proposed that our sense of self is more resilient when it is made up of many distinct parts. Her research showed that people with more complex self-structures were better able to absorb setbacks – emotionally steadier and less vulnerable to the strain that prolonged stress can bring. Later work by Rafaeli-Mor and Steinberg suggested that such diversity can also act as a social buffer, offering more than one source of belonging when change arrives. The reasoning is intuitive: if your sense of self is spread across several domains, a loss in one does not undo the whole.

In practice, this means a balanced identity portfolio works a lot like a balanced investment portfolio. A few strong holdings – family, friendship, service to others – can offset the volatility of any single one. Ideally, identity broadens before retirement – new roles developing while the old title still lends structure. But it’s equally possible, and powerful, to do it after. The aim is not to rehearse a clever line for parties – ‘I’m a former marketing executive turned golfer’ – but to cultivate multiple, authentic selves that hold real meaning, a genuine diversification that we embody and can articulate with confidence.

We may intuitively understand the logic of diversification, yet few of us pause and examine – and, indeed, rebalance – the actual composition of our own lives. To build a more balanced identity portfolio, it helps to take stock: to see, quite literally, where our current selves sit and how they connect. The two exercises that follow – one visual, one verbal – offer a way to trace where the self still holds weight and where it may be time to invest anew.

The Identity deck

For years, we built decks to persuade others: to sell ideas, justify budgets, win approval. The identity deck asks for the opposite: to take stock rather than sell, to understand rather than convince. It’s not for clients or colleagues, but for ourselves – a quiet inventory of who we are beyond the job title and what still gives life its shape. A degree of clarity can be achieved in just four simple steps:

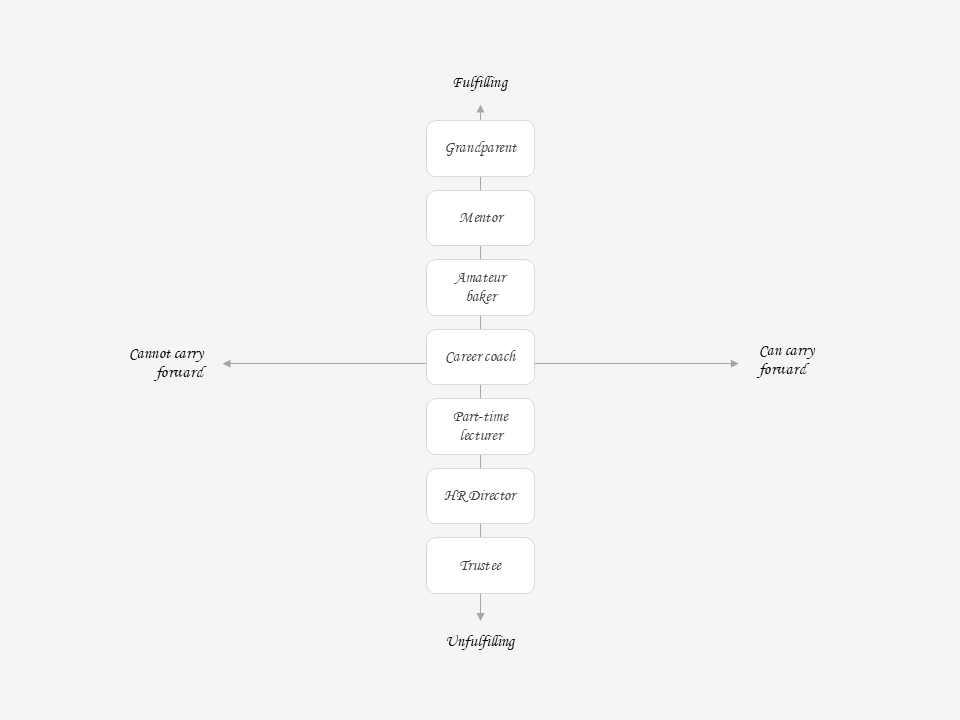

- Surface identities

Take 5–10 index cards or sticky notes. Write one self-aspect per card – roles that are active, less active, or ones you’d like to explore: mentor, trustee of a local charity, amateur gardener, (grand)parent and so on.

- Plot fulfilment

Place your cards on the grid along the vertical axis – from fulfilling at the top to unfulfilling at the bottom. This arrangement reflects how each role feels or might feel in practice – whether it brings vitality and meaning or feels more like duty and fatigue.

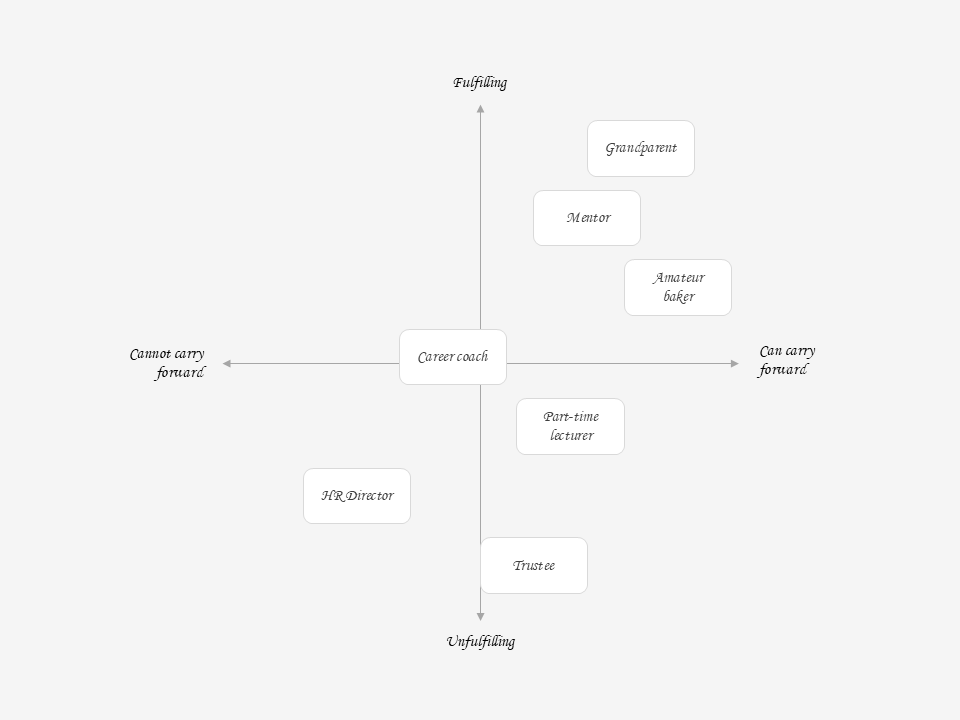

- Calibrate intention

Next, slide each card along the horizontal axis – from cannot carry forward on the left to can carry forward on the right. As you do, consider your wider circumstances: health, finances, relationships and aspirations. Be realistic, but let a little room remain for what you still hope to grow into.

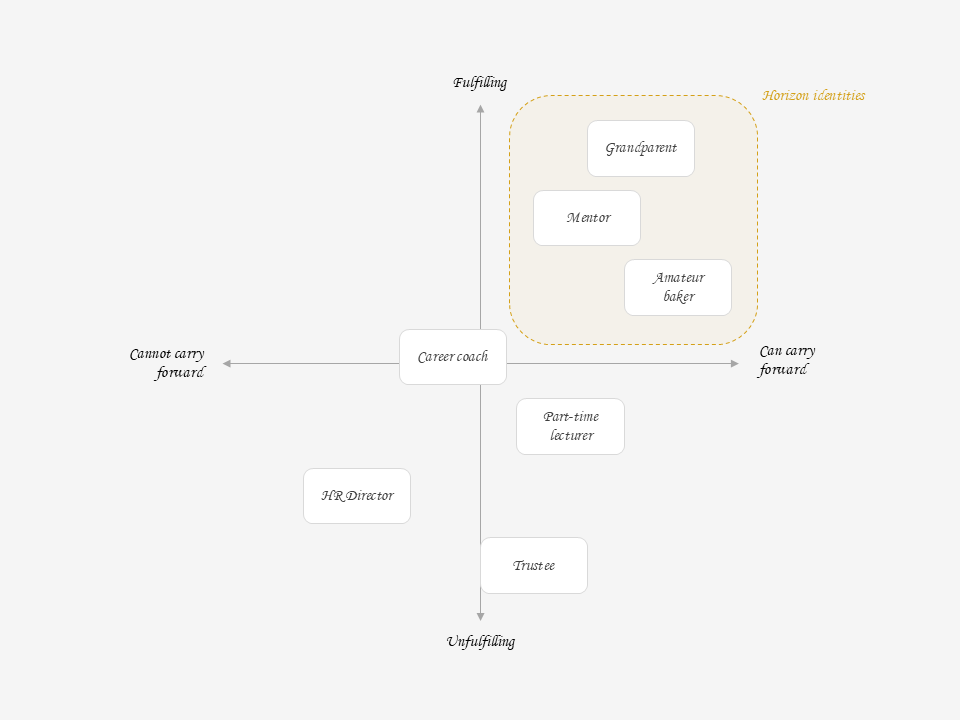

Locate horizon identities

Survey your map of identities and notice where each role has settled. The ones clustered in the upper-right quadrant – fulfilling and possible to carry forward – are your horizon identities: those that hold the greatest potential for renewal and future investment.

If you end up with several horizon identities, choose up to three you'd like to focus on moving forward: it is often depth, rather than breadth, that sustains fulfilment over time. If, on the other hand, the space feels sparse or empty, return to your cards and ask yourself: Who would I be without limits? What have I put off doing for too long? What early interests still feel alive? You may find that the answers which surface are not new at all, but long-standing desires – the very things that could bring the deepest sense of purpose and satisfaction in later life.

The Reintroduction

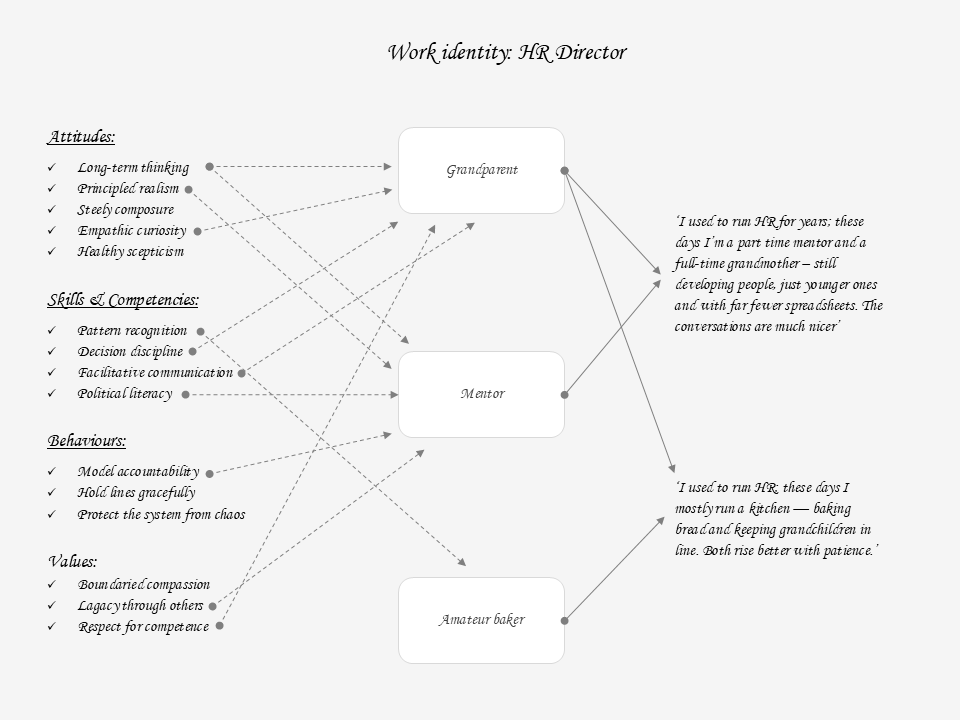

The Reintroduction builds on the identity deck, translating the visual back into words. Its aim is twofold: to see how your working identity can evolve – which qualities still serve you and which may take new form – and to find language that feels both present and true – a short description of who you are now or hoping to become.

- Revisit your work identity

Take a new paper sheet and write Work identity somewhere along the top. Next, list the attitudes, skills, behaviours and other attributes that define or have defined you in that role.

- Connect horizon identities

Place your horizon identities cards nearby. Begin to draw lines and make notes where you can trace emerging connections. Notice which qualities seem to carry over naturally and which stand in contrast. For example, a management consultant, exploring her 'gardener' identity, might find that the instinct for structure and analysis now guides how she plants hollyhocks, though the drive for constant optimisation has given way to patience and quiet observation.

- Craft your reintroduction

Now, draw your insights together in a short self-description – a few sentences that feel natural to say aloud. A good reintroduction often weaves together three strands:

- What you did: the work or focus that once defined you

- What you do now: how elements of that identity have evolved or found new form

- Why you do it: the value or meaning it brings to you or those around you

Psychologically, these three elements mirror how we build a coherent sense of self over time: continuity provides stability, change reflects growth, and purpose gives both direction and depth. Together, they form a narrative that connects who we were with who we are becoming:

'I spent years helping organisations grow more efficient. These days, I apply the same curiosity to growing food and mentoring others – it’s still about nurturing things, just on a different scale.'

'I used to manage teams and projects; now I channel that same energy into running community workshops at a local church. I still build things – just with people rather than products.'

The aim isn’t to craft a slogan, but to find a voice that feels lived-in – something that links your past expertise with your present rhythm of life. When language aligns with identity, conversations start to flow again. And sometimes, that clarity reveals itself in the simplest of places – at a wedding table, perhaps, when someone leans in with the familiar question: “So, what do you do?”

Back in the marquee, the same question drifts across the table once more. But something subtle has shifted – the answer now carries ease, not explanation.

“I used to be a chemistry teacher, now I’m a baker – but the kind who knows exactly what’s happening in the oven. My grandchildren love it: they get warm bread and a light-hearted lesson in chemistry.”

“No way, I once applied for Bake Off! Do you watch the show?”

And just like that, the conversation moves – easy, natural, unforced. The awkward pause has turned into connection, a quiet reminder that paying attention to our identity portfolio is every bit as important as tending our financial one. Both need rebalancing, both reward patience and both promise dividends – only one is measured not in hard currency, but in purpose. The returns come quietly, in the ease of conversation, the spark of curiosity, the warmth of a new role that feels entirely our own. And, as it turns out, it pays off rather nicely at a garden party.

References:

- Berger, J., Cohen, B. P., & Zelditch, M. (1972). Status characteristics and social interaction. American Sociological Review, 37(3), 241–255.

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

- Linville, P. W. (1985). Self-complexity and affective extremity: Cognitive complexity and affective experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(3), 663–676.

- Linville, P. W. (1987). Self-complexity as a cognitive buffer against stress-related illness and depression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(4), 663–676.

- Rafaeli-Mor, E., & Steinberg, J. (2002). Self-complexity and well-being: A review and research synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 31–58.